Assistive Technology for Dyslexia in Arabic:

Encouraging this Old Dog to start thinking about New Tricks!

|

| Dyslexia in Arabic - is it that Different? |

For those of us who have spent the greater part of our

careers working in one language, such as English, one of the most interesting

things about working in a new culture is how we are forced to disassemble all

we assume and all we think we know about Dyslexia.

I’ve just spent an unbelievably interesting day, trying to

gain a greater insight as to how Dyslexia represents itself when a child or

adult is reading or writing in Arabic.

When I arrived in Doha two years ago I grappled with

learning Arabic. My enthusiasm was

without question; my ability however fell a lot shorter. This was my starting point in appreciating the profound differences between not just both languages but how people learn or teach each of these languages.

For the first time, I became truly aware that how a language is learnt is guided not just by the trends and fashions of teaching but also by the language itself.

Thinking about this in the context of finding technology to support those with Dyslexia in Arabic - for an English speaker was truly an onion worth peeling, in spite of the anticipated tears!

Dyslexia is often described as a specific learning difficulty

and as such it reveals itself in many different ways. Dyslexia is not just a

difficulty with words, or the ability to read and write. As such, the use of technology that only helps

with spelling and reading often disregards some underlying difficulties that

may be impacting the natural development of these skills.

(Click on the link below to learn more)

Often Dyslexia is inaccurately characterized as being a

diagnosis of convenience for children who are just poor at spelling, reading or

handwriting which can be fixed by practice, effort, hard work and when all else

fails a good old spellchecker.

For anyone with Dyslexia however, and for those of us who

have worked first hand with children and adults with this learning difficulty

the reality is much more nuanced, much more complicated and requires more

sophisticated solutions. We have, over

time watched the software and technology mature, and we’ve seen developments come and go, but for English Speakers with Dyslexia, there are real valuable tools out there. Word Prediction, Text to Speech, Object Character Recognition software, Software supporting multi-sensory learning are now common tools. Software titles such as Kurzweil 3000, Text Help, Co-Writer, Penfriend, Ginger, Claroread and a multitude of other titles have become household names, insofar as is possible in the AT community.

Moving to work in a space where Arabic is the primary

language used in community life, and for the most part in Education, it forces

us to challenge all that we think we know about Dyslexia. This has been one of the times, where I have

had to reflect on how I have developed my belief system about assessment for

Dyslexia and how technology can best meet the needs of children and adults

struggling with print literacy.

(Click on the link below for more information on Dyslexia

and Arabic)

Today I spent some time in the company of a new friend and

colleague, Dr Gad Elbeheri, a lecturer in the Australian University in Kuwait

who has an appreciation for and understanding of Dyslexia in Arabic based on

his research and investigation over the past number of years. What was most interesting to me was how he

explained how the sound of a language often dictates how it is traditionally

taught. He confirmed for me something I

was beginning to suspect, i.e., the primacy of traditional literacy teaching based

on auditory skills that we see in English language education is not as applicable

when learning Arabic. Of more interest

to me was the fact that, although I knew that written Arabic is a morphological

language, which has a transformative quality based on context etc., creates

another layer of abstraction for students struggling with learning.

We spoke at length about predictors for development of good

functional literacy in English and in Arabic and compared stories of

experiences we had.

So what does this have to do with Assistive Technology?

In English we have a history of using technology to address

Dyslexia which stretched back till at least the early 90’s if not before.

For more information click on this link: http://dyslexiahelp.umich.edu/tools/software-assistive-technology

.

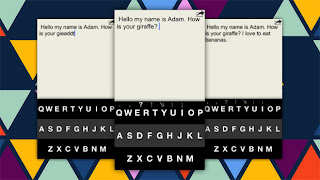

However, as the Assistive Technology industry in the Arabic

speaking world has not had as much time to mature, there is not the same range

of solutions available for people. Over

the past two years, Mada has tried to address this issues by supporting the

development and localization of specific software products aimed at directly supporting

those with Dyslexia, including and Arabic version of Clicker 5, an Arabic Claroread

and an Arabic

version of the FXC Open source Utilities.

There are many challenges ahead, in particular tacking

Object Character Recognition and Voice Recognition software, particularly for

those requiring compensatory strategies.

With challenges, however there are opportunities.

One thing that struck me today was the value of conversation

and debate, a few hours in the company of a knowledgeable and generous

colleague is worth weeks of research.

Debate and discussion is healthy and productive.

Most importantly we both agreed on several points:

- 1. There is a real and immediate demand for technology that will support those with Dyslexia

- 2. The technology cannot just focus on compensation, as doing so would deny many children the significant benefits that can be gained through learning with a technology partner.

- 3. New technology developed must be based on research and data as to how Dyslexia manifests in those learning to read and write in Arabic.

- 4. Bringing academics, technologists, educators and children together will be the key to developing good solutions.

There is nothing new in this, nothing we haven’t considered

before, I have however grateful for the opportunity to talk with a colleague

and in partnership re-affirm a road forward in being part of the process of

ensuring that technology can be used to minimize the difficulties and maximize

the opportunities for people with Dyslexia.

For more information feel free to click on the links below: